In the Eastern Han Dynasty, Hua Tuo’s ‘Shi Jing’ mentioned ‘bitter tea, long-term consumption, benefits the mind,’ documenting the medicinal value of tea. This is akin to Coca-Cola, which initially appeared as a headache remedy before evolving into a beverage. Later, a prototype of fried tea, known as porridge tea, emerged in folk culture. According to Zhang Ji’s ‘Guang Ya’ from the Wei state during the Three Kingdoms period, Sichuan people picked certain leaves, shaped the old ones into cakes, and covered them with thick rice paste.

To drink, the cakes were soaked in rice soup, toasted over flameless charcoal until they turned red and dried, then crushed into a fine powder and placed in a porcelain pot, infused with boiling water. Some added green onions, ginger, and oranges to balance the bitter taste. This tea was different from what we drink today; it was more like a spicy soup, with those who liked it finding the taste quite special, and those who did not, finding it hard to swallow. The tea saint of the Tang Dynasty, Lu Yu, criticized this ‘spicy soup’ by saying: ‘Boiled with onions, ginger, dates, orange peel, cornelian cherry, and mint, it’s like discarding water from the ditch after boiling it a hundred times, or skimming it to make it smooth, or boiling off the foam, this is the water thrown away between the ditches!’ During the Six Dynasties, porridge tea became a popular drink in the south, with Sun Hao of Wu often replacing wine with tea at banquets, and Huan Wen also used tea banquets to showcase his frugality. However, northern guests could not accept porridge tea and generally drank dairy beverages, mocking tea as ‘cheese slave.’ In the Tang Dynasty, the Chinese began to drink tea using the frying method. Due to the emergence of the frying method, the custom of drinking tea flourished throughout the Jiangnan region, ‘between Kaiyuan and Tianbao, there was a little tea, and it became more during the De and Dali periods, and it flourished after Jianzhong. ‘ After the mid-Tang Dynasty, tea had entered the civilian sphere, becoming a popular beverage among the common people. The transformation of tea’s fate is attributed to the tea saint, Lu Yu. ‘Since Lu Yu was born among people, people have learned to appreciate spring tea.’ Lu Yu wrote ‘The Classic of Tea’ in three volumes, providing a detailed discussion on the tea ceremony. He advocated drinking powdered tea made from crushed tea cakes, with the tea powder being the size of rice grains. First, before frying tea, one should roast the tea, holding the tea cake over high heat and frequently turning it, ‘repeatedly turning it over,’ otherwise, it would be ‘unevenly heated,’ and it is appropriate when the tea cake shows a ‘toad’s back’ shape. The roasted tea should be wrapped while still hot to prevent the aroma from dissipating, and then ground into fine powder after the tea cake cools.At the same time, fresh spring water was boiled in a tea pot. When it reached the stage of ‘fish eyes’ bubbles and a slight sound, which is ‘the first boil,’ salt was added for seasoning and the water film resembling ‘black mica’ on the surface was removed, otherwise ‘the taste would not be correct.’ Then, continue to boil until bubbles form at the edge of the water like ‘springing pearls,’ which is ‘the second boil.’ First, scoop out a ladle of water from the pot, then stir the boiling water with a bamboo spatula while adding the ground tea powder.

When the tea soup in the pot bubbles vigorously like ‘billowing waves and surging tides’, which is the ‘third boil’, add the ladle of water scooped out during the ‘second boil’ to temporarily halt the boiling, allowing the tea to ‘nourish its essence’. Only then is the tea soup considered well-brewed and ready to be served. Why is the emergence of ‘The Classic of Tea’ considered the birth of Chinese tea culture? Because the method of boiling tea allowed for the earliest artistic consumption of tea to take shape.

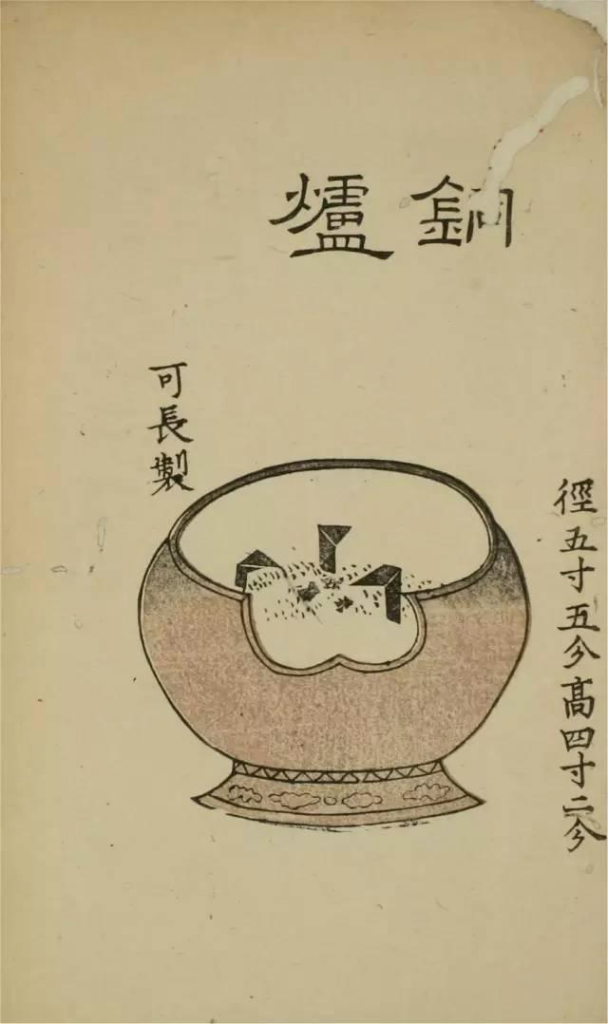

When boiling tea, one must pay attention not only to the ‘heat’ but also to the ‘soup timing’, determining how long the water should be boiled. To discern the soup timing, one looks at the quantity and size of the bubbles when the water boils, and listens to the sound of the boiling water. ‘The Classic of Tea’ states that water should be boiled but not too old, as this would destroy the beneficial components in high-quality spring water that are good for the human body. Brewing tea with such ‘old soup’ results in a tea soup that lacks brightness in color and richness in taste, giving a dull sensation. Some high-grade green teas are even more sensitive to the temperature of the brewing water; water that is too hot can cook the delicate tea buds, destroying the beneficial components within the tea and being detrimental to the hygiene of tea drinking. On the other hand, using water that is too cold to brew tea results in an underdeveloped ‘young soup’, which fails to extract the various effective components from the tea leaves quickly or completely. Tea brewed with this ‘young soup’ is weak in flavor and poor in color. Lu Yu also advocated for drinking tea while it is hot, asthe ‘ heavy and turbid settles below, while the essence floats above’. Once the tea cools, ‘the essence follows the air and dissipates, and drinking it will not be refreshing.’ Additionally, the first bowl of tea soup scooped out is considered the best, known as ‘jueyong’, with the quality decreasing thereafter, until by the fourth or fifth bowl, the tea flavor is virtually gone. ‘Dream of the Red Chamber’ mentions, ‘One cup is for tasting, two cups are for quenching thirst, and three cups are for drinking like a cow.’ After Lu Yu, the method of boiling tea continued to be refined and expanded upon. Fei Wen wrote ‘Tea Description’, Zhang Youxin wrote ‘Boiling Tea Water Records’, Wen Tingyun wrote ‘Tea Picking Records’, and Jiao Ran and Lu Tong composed tea songs, all contributing to the maturation of Chinese tea boiling methods. The art of tea now includes five fixed steps: preparing the utensils, selecting water, obtaining fire, timing the soup, and practicing tea. Today, the Japanese tea boiling method has preserved the essence of the Chinese method and innovated upon it. ‘Tea Seller’s Tea Utensils Illustration’ shows the Tang Dynasty’s copper stove and the Song Dynasty’s tea dotting method. In the late Tang Dynasty, the Tang people invented a ‘tea dotting method’, which involves using a small spoon to distribute tea powder into several bowls, pouring in boiling water while quickly stirring to ensure the tea powder mixes thoroughly with the water. The resulting tea soup will have a layer of creamy white foam on top, with the best being fresh white foam that gathers and does not dissipate quickly. By observing the brewed tea, one can judge the skill level of the tea maker. The tea dotting method can highlight the characteristics of powdered tea, and there are many nuances and techniques involved in controlling the water flow, volume, and point of impact when pouring. However, the ‘tea dotting method’ only became the mainstream way of drinking tea during the Song Dynasty.During the Song Dynasty, people placed great emphasis on tea cakes, pursuing a flavor profile of ‘fragrant, sweet, heavy, and smooth’, avoiding the bitter and astringent original taste of tea. They valued tea with a ‘pure white color as the ultimate truth’. To create the ideal tea cake, they strived for perfection in craftsmanship. First, they carefully selected the raw materials, only taking the heart of the tea leaves, soaking them in spring water, then steaming them in a pot.

After steaming, they used a small press to remove the water and a larger press to extract the tea juice, aiming for a white color and a sweet taste. After pressing, the tea was ground in a basin. A good tea cake usually required grinding for more than a day until the paste in the basin was smooth and delicate. Then, camphor and other spices, along with a thin porridge made from fragrant rice, were added and kneaded together to form the tea cake. Liu Songnian’s ‘Grinding Tea Picture’ from the Southern Song Dynasty illustrates the meticulous process involved in tea making cakes. Due to the addition of starch, the tea cakes resembled milk, and with the incorporation of spices, they had a sweet and fragrant taste, which was completely different from the salty soup tea of the porridge tea method. Tea cakes made by tea masters were as expensive as school district houses. During the reign of Emperor Renzong of Song, Cai Xiang’s ‘Xiao Long Tuan’ sold for two taels of gold per catty and was extremely hard to obtain. People at the time said, ‘Gold can be had, but tea cannot be obtained.’ During the reign of Emperor Huizong of Song, Zheng Ke made ‘Long Tuan Sheng Xue’ with ‘silver silk water buds’. Each cake was not only priced at 40,000 coins but also required a limited sale lottery. At that time, people were also very particular about the tea brewing process. First, the tea cake had to be dried and crushed, then ground into fine tea powder with a tea mill, with the smaller mill the, the better. The tea powder was then sifted through a sieve into a tea canister, ready for use. Next, the tea bowl was preheated to avoid the temperature drop caused by pouring hot water into a cold bowl, which would affect the taste. After preheating the tea bowl, a long-handled spoon was used to scoop tea powder from the canister into the bowl, and a small amount of boiling water was added to mix the tea powder evenly. Then, a teapot with a long spout was used to pour water while stirring with chopsticks, a long-handled spoon, or a bamboo whisk to mix well. After stirring, more water was added, with the standard being the ‘initial boiling water’ described as ‘crab eyes have passed, fish eyes are emerging, and the sound is like the rustling of pine wind’. The final step was to adjust the tea, which required ‘first stirring the tea paste, gradually adding boiling water, light whisk, heavy bamboo whisk, and fingers around the wrist’, to achieve ‘thoroughly mixed up and down, like the rising of fermented dough. Sparse stars and bright moon, shining brightly’, until the tea surface was filled with silver light, indicating that a cup of tea was well brewed. Due to the meticulous technique required for tea brewing, it was a true technical task, so the wealthy and leisurely people of the Song Dynasty often took pleasure in ‘tea dueling’, comparing their skills in a competition format multiple where people fought together or two people fought each other, with the best two out of three wins. Tea dueling mainly assessed the integration of tea and water, stirring the tea to rotate, and the first to leave a mark on the tea bowl was considered the loser. Tea with a pure white color was most noticeable when served in black bowls, so black tea bowls produced by the Jian kilns in Jianyang, Fujian, were the most popular at the time.Su Shi and Su Zhe, brothers, enjoyed engaging in tea dueling and even composed poems about it.

During the Yuan and Ming dynasties, the art of tea brewing was less emphasized. As the tea-drinking community expanded, the Chinese became less particular about the tea ceremony, as boiling tea was too time-consuming and labor-intensive. Instead, they opted for a simpler method of steeping tea leaves directly in water. Since then, after harvesting, Chinese people would dry the tea leaves and brew them directly in teapots, without mixing in starch or spices, and without making tea cakes or grinding them into powder. The complex tea utensils used for making powdered tea also disappeared, with only the long-spouted tea bottle for holding boiling water transforming into a teapot, which continued to be used. In the Ming dynasty, emperors favored brewing tea. During the Hongwu reign, the court advocated for frugality and banned the production of high-grade tea cakes, leading to the dominance of loose tea. As everyone started brewing tea, the craftsmanship of teapots evolved with the times. The breathability of purple sand clay made it suitable for brewing tea, and a new tea culture began to flourish. Purple sand teapots rose to prominence in the Ming dynasty, favored by both emperors and commoners. These pots were also portable and beloved by literati, remaining popular to this day. The shift from porridge tea, frying tea, and tea dusting to brewing tea reflects the transformation of ancient lifestyles. However, in modern society, many still adhere to the ancient methods of frying and dusting tea. Yuan tomb murals: Tea Ceremony Diagram Conclusion: In essence, the tea ceremony is life itself. From a single leaf of tea to a cup, a table, a room, a city, and a nation, tea has become integrated into human lifestyles. Nowadays, people pursue simplicity and efficiency, and in the haste of life, tea drinking seems to become increasingly simple. Yet, the simplification of tea drinking methods has led to a higher spiritual pursuit: simplicity and elegance, which is the beauty of simplicity, the beauty of life. Brewing tea in a teacup, the lingering cultural atmosphere, is a glimpse into Chinese aesthetics. May everyone reserve some time for themselves to enjoy tea, calligraphy, painting, or engage in some refined activities, allowing the aspiration for a beautiful life to be fulfilled.